Sarah Phillips credits fossil fuels for giving her her daughter, Sunny Bella Phillips. Complications during labor nearly killed Phillips and Sunny. But Phillips, a petroleum engineer, said they survived because of the hydrocarbons—also known as fossil fuels—that created and powered the medical technology that delivered Sunny safely into the world.

“If you walk into a hospital, there are few things—if anything—that you can touch or see that isn’t a derivative of oil and gas,” Phillips said, elaborating that “the four pillars of the modern world—cement, steel, plastics, fertilizers—are all due to oil and gas.”

If not for these modern technologies and reliable energy, the emergency Caesarean section that brought Sunny into this world would not have been possible, she said—and neither would have any of the medical interventions along the way that helped Phillips deliver her daughter.

The first sign something was wrong during Phillips’ labor was eight days after her due date when her blood pressure came back high during a checkup.

“My blood pressure is never high,” Phillips told IW Features. “It’s always low.”

When the doctor came in, Phillips said she was told she needed to be induced right away. She said she was sent home with medication to thin her cervix, and when she arrived at the hospital to give birth, her body had already gone into natural labor. Then, her water broke, the contractions increased, and her cervix dilated extremely quickly, she said. Her blood pressure also dropped dangerously low, and her baby’s heart rate dropped.

“They gave me medicine to increase my blood pressure, which vicariously increased my baby’s heart rate,” Phillips said. “Then I got the epidural. I was in no more pain. They stabilized me.”

Phillips was told to wait until she felt the instinct to push, but the next day, she said the doctors told her she needed to start pushing on her own.

“For—I think—two hours, I was pushing on my own as hard as I could,” she said. “During this time, my blood pressure dipped again, and the baby’s heart rate dipped again to dangerously low levels. And then the doctor walked in, and she said, ‘Sarah, we need to have an emergency C-section.’”

In the operating room, Phillips said she could feel more pain than she was supposed to, despite having a high pain tolerance.

“I looked at my husband, and I said, ‘I can feel it. I can feel it,’” she said. “That was one of the most terrifying moments in my life.”

Despite her harrowing experience, Phillips emphasized just how fortunate she and her family were to have this life-saving procedure—and the role that hydrocarbons played in saving her daughter’s life.

After being told she needed a C-section, Phillips recalled asking the doctor, “‘Did you know that 200 years ago, the global child mortality rate was 46%?’ Most mothers had a one in two chance of seeing their babies survive.”

“The doctor turned to me, and without missing a beat, she intuitively said, ‘Yes, I did know that, but the mothers also died too,’” Phillips added.

It was Alex Epstein’s book Fossil Future that opened her eyes to this connection between energy poverty and infant mortality, Phillips shared.

“I was reading about this doctor who was on tour, and he was touring all of these energy impoverished nations,” she said. “He witnessed this woman give birth to a baby… And this woman had to watch her baby die needlessly because she didn’t have access to an incubator because they didn’t have access to energy to power it.”

“I just thought how heartbreaking and gut wrenching that was,” she added, “especially now imagining watching my baby die.”

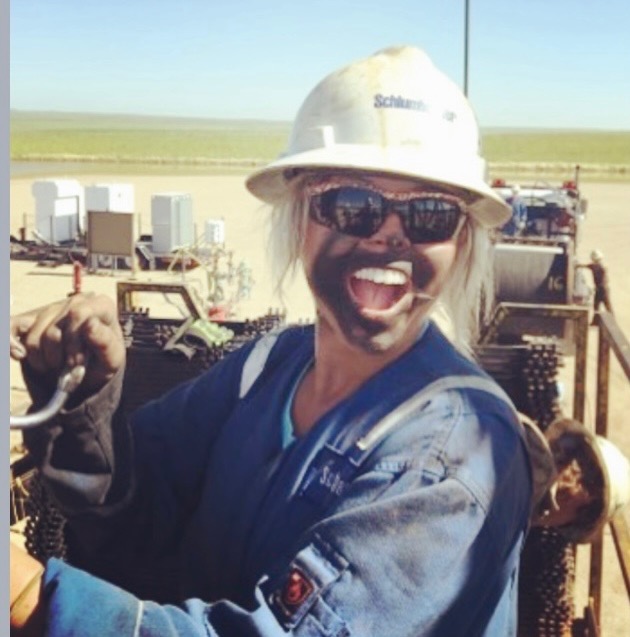

However, Phillips wasn’t always pro–fossil fuels. Growing up in a liberal family and in Morgantown, West Virginia, a liberal town, she said it wasn’t until college that she began to reconsider her ideas. While studying business, she bartended on the side and said that her favorite patrons worked in oil and gas.

“They were gritty,” she said. “They were honest. They were transparent. I really liked the vibes and the culture.”

When she stumbled across a job in the oil and gas industry, Phillips said she fell in love with the field and decided to become a petroleum engineer.

But despite her career path, Phillips said her family still accepts the anti–fossil fuel narrative.

“My family, they’re good people. And the whole reason why they believe this narrative is because they’re good people, and they care about the less fortunate,” Phillips shared.

However, Phillips believes that being pro–fossil fuels is the compassionate and environmentally friendly position. Renewables don’t offer the scalability, affordability, or reliability that billions of people need, she said.

“If you compare food to energy, renewables is like caviar,” Phillips elaborated, using the rare and expensive food as a metaphor, “while Americans are living on steak and potatoes.”

Meanwhile, in the third world, where oil and gas are harder to come by, biomass is a common fuel source, but it burns “dirty” and contributes to millions of deaths each year from particulate matter inhalation.

“Two billion people on the planet are cooking with [biomass like] wood and dung,” Phillips explained. “It’s adversely affecting women because they’re the ones collecting the wood and cooking with the wood… and their children are inhaling particulate matters.”

In comparison, she explained how fossil fuels can offer a reliable and cleaner energy source. For instance, she pointed to natural gas’s role in the U.S. leading the way in reducing carbon emissions. Indeed, one of the largest natural gas fields, Marcellus Shale, is located across Pennsylvania, Ohio, West Virginia, New York, and some parts of surrounding states, and the natural gas there could power the U.S. for hundreds of years.

“If West Virginia, Ohio, and Pennsylvania were its own country, it would be the third most natural gas producing country in the world,” Phillips detailed.

The company she works for, Gladiator Energy, provides key services for energy extraction in the area. “And as technology advances, we’re going to be able to find out more ways to extract this resource,” she added.

For women cooking with biomass, even propane fuel would be lifechanging—and lifesaving.

As a counter to so-called “green” initiatives, Phillips mentioned Energy Corps’ 50-50-50 vision to ensure each person has access to 50 megawatt hours of electricity per year, to increase global per capita GDP to $50,000, and to “maximize modern energy in 50 years.”

Rather than decreasing energy usage, Phillips believes we need to increase the affordability of energy so that energy is more accessible to impoverished people. To achieve this goal, she suggested letting market forces lead the way, rather than relying on the government to subsidize certain energy sources.

“The renewable percentage of our global energy hasn’t changed,” Phillips said. “But billions of dollars are being poured into it.”

For example, she cited the 2022 Inflation Reduction Act, which allocated $369 billion to climate and green energy initiatives. President Donald Trump’s Working Families Tax Cut Bill (aka The One Big Beautiful Bill Act) has since rolled back much of these funds.

Phillips is so passionate about this topic that she is writing a book about her time in the field. But most of all, she emphasized how fortunate she and her daughter are to live in a country with reliable fossil-fuel energy.

“We live in a life of luxury, and we should be very thankful for it due to hydrocarbons,” she said.