When James Zimmermann was invited to audition for the Knoxville Symphony Orchestra in 2025, he had no idea it would reignite a years-old woke firestorm that had ended in his firing from the Nashville Symphony Orchestra.

Zimmermann spent about 100 hours getting into “fighting shape” on the clarinet for the Knoxville audition, after taking a five year break from full-time professional playing and entering a career in software writing following his dismissal from the Nashville Symphony.

However, Zimmermann’s career was not on hold because it was unsuccessful. His music has been heard on TV shows like Netflix’s “My Little Pony,” former President Barack Obama’s inauguration, video games like “The Last of Us” and “Call of Duty,” and Disney World’s theme “Begin the Beguine.”

“I turned in a very dominant performance,” Zimmermann said of the blind audition at Knoxville in an interview with IW Features. “I was the leading candidate the whole way, I heard afterwards. And ultimately, I won by unanimous vote in the finals. The audition coordinator said, ‘We’ll call you tomorrow and we’ll get you on the payroll in two weeks.’”

But the Knoxville Symphony Orchestra eventually hired the runner-up from the blind audition—someone whom Zimmermann described as “an obvious DEI hire.”

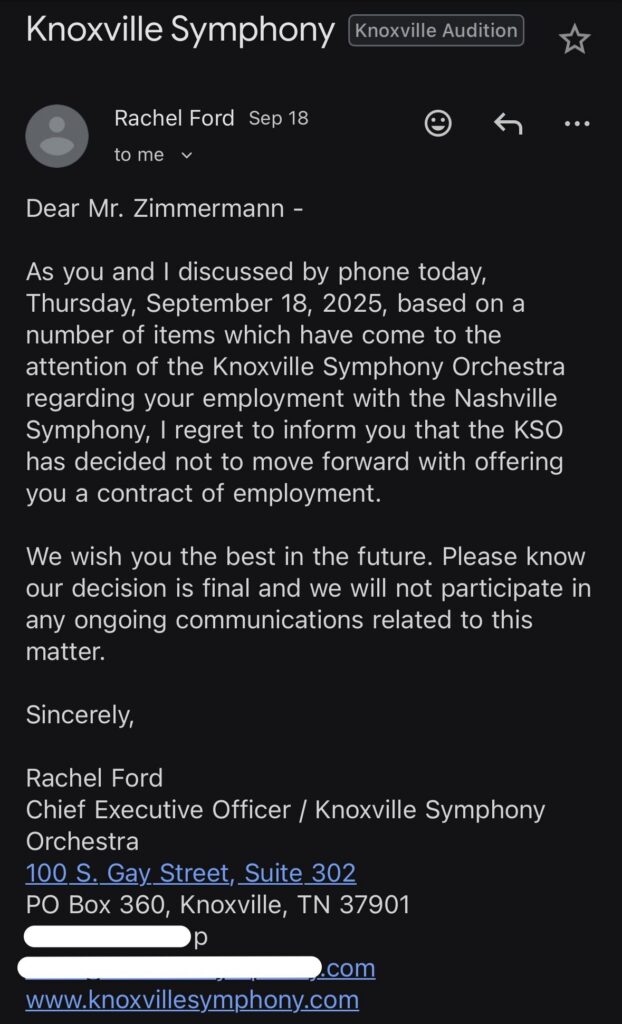

In an email reviewed by IW Features, the orchestra’s CEO cited as reason for his being passed over for the job “a number of items which have come to the attention of the Knoxville Symphony Orchestra regarding your employment with the Nashville Symphony.”

Zimmermann described the circumstances leading up to his firing in Nashville as a sordid love affair with DEI in the symphony that began around 2017.

“They hired a temporary principal oboist who was black, a guy named Titus Underwood,” Zimmermann recalled. “He was a journeyman oboist who had never been able to win a professional audition. He was a pretty good player. He had a lot of talent, but he’s ideologically deranged, socially awkward, and very activist in nature, putting the orchestra through diversity luncheon struggle sessions. There’s tons of media out there of him, you know, explaining his terrible experiences with racism throughout orchestras.”

In a video released on Bloomberg News’ YouTube channel in July 2020, Underwood described his experiences with an unnamed person in the Nashville Symphony Orchestra who “racialized our conversations” and began “antagonizing” him even to the point of “sub-coded physical threats.”

“The orchestra then took the right initiative because they did anti-racism training,” Underwood said in the video. “I’ve been having these conversations with the organization for the past two years about how to recognize these things.”

Bloomberg’s video then mentioned that the “individual” in question was fired from the orchestra—a line which Zimmermann said is an obvious reference to himself.

But Zimmermann tells a very different story about the firing.. As industries across the country clamored to prove their diversity bonafides during 2020, Zimmerman said classical music succumbed to the psychosis, pushing to get rid of blind auditions. Zimmermann took a principled stand to keep blind auditions, the traditional method by which musician seats are awarded in an orchestra, but the Nashville Symphony began awarding seats based on other criteria.

These criteria came into play with the orchestra’s decision to give Underwood a permanent spot, Zimmermann said.

Underwood had been awarded a temporary spot with the orchestra in 2017, but the oboist still needed to win a blind audition to receive a permanent spot. During the final round of blind auditions for the permanent position, Underwood was the tentative favorite, but the judges still had their doubts, resolving to offer him a trial period.

However, a snafu during the audition revealed Underwood’s identity, tipping the scales against him. The problem, according to Zimmermann, wasn’t that the judges were racist, but that Underwood had been struggling in performances since he entered the orchestra years earlier.

Still. Zimmermann stuck his neck out for Underwood, arguing that the judges should go with their initial inclination during the blind audition to offer Underwood a trial period.

Then, in a strange about-face due to what Zimmermann described as a woke panic, the symphony’s maestro, Giancarlo Guerrero, who had initially led the charge against offering a permanent spot to Underwood, awarded him the position without even waiting for him to prove his bonafides and without a vote from the committee.

Zimmermann questioned the symphony’s decision and whether it had to do with their recent commitment to promoting diversity. As a result, Underwood reported Zimmermann, even though Zimmermann had “singlehandedly saved [his] career that day by standing up to all of his colleagues.” But Zimmermann’s “anti-DEI stances, my outspokeness” had put a target on his back, he said.

“It was totally a smoke screen for the fact that [Underwood] failed the audition process,” Zimmermann argued.

Underwood wasn’t the only orchestra member who took issue with Zimmermann’s opposition to DEI, and a series of misunderstandings led to increased tensions, he admitted. In one instance, Zimmermann asked another orchestra member who lived in his neighborhood if he was hosting a party because he saw lots of cars in his driveway. Zimmermann had also asked Underwood some questions about where he lived because he was thinking of moving to the area, an action which Underwood interpreted as potentially obsessive.

His difficult relationships with his coworkers led created a whirlwind of stress, which Zimmermann said led him to write an email he describes as “ill-advised” late at night in February 2020. In one section, Zimmermann noted that his family owned a gun.

“I saw it as a cry for help,” one of Zimmermann’s colleagues said of the email, according to a report from the Washington Free Beacon.

Zimmermann was placed on leave and eventually fired. Six orchestra members interviewed by the Washington Free Beacon said they did not interpret the email as threatening violence, with one brass player claiming that the firing was an effort to bury the story about Underwood’s audition.

Management offered Zimmermann $30,000 to keep silent and sign a nondisclosure agreement. He declined.

Five years later, Zimmermann decided he was ready to finally try and reenter the world of professional music by auditioning for the Knoxville Symphony Orchestra.

“I just want to put this whole nonsense of 2020 behind me,” Zimmermann said. “The times have changed. I’d just like to go back into an orchestra and earn some money playing my horn, stock it away from my kids’ college, and be doing what I love again. I miss playing in the orchestra all the time. It’s a very enjoyable profession, and it’s a great privilege to be able to earn money playing. I write software now. It’s boring, you know.”

That’s what made the Knoxville Symphony Orchestra’s sudden rejection of him so disappointing, Zimmermann said. He had earned that spot through his audition, he argued, which suggests the decision was ideologically motivated.

To that end, Zimmermann and his lawyer dropped a lawsuit against the Knoxville Symphony Orchestra shortly before Christmas.

“Mr. Zimmermann is entitled to reliance damages based on the Orchestra’s violation of its promise to base hiring decisions on the results of a screened audition,” the lawsuit, which was reviewed by IW Features, reads. “Even though Mr. Zimmermann rehearsed for that audition for nearly 100 hours by practicing the Orchestra’s specialized Repertoire, and he prevailed in three rounds of screened auditions to be recognized as the prevailing candidate, the Orchestra refused to hire him based on facts and/or characteristics about Mr. Zimmermann that were both knowable and actually known to Orchestra agents in advance of the audition and irrelevant to the quality of his music.”

“Had Zimmermann not been a white male, particularly a white male who had previously expressed opposition to DEI initiatives, the Orchestra would have proceeded with hiring him consistent with the result of its screened auditions,” the lawsuit alleges.

Zimmermann is seeking damages of $47,476, the amount he would have been paid as the principal clarinetest at the orchestra, and $25,000 to compensate time spent practicing for the audition, as well as recompense for attorney fees and costs.

“I think that the blind audition is the most meritocratic process imaginable for giving someone a job,” Zimmerman said. “If you can play, we will hire you. We don’t care if you’re gay or black or straight or trans or conservative or liberal, or full of tattoos, or you have blue hair, like we just don’t care about any of those things. We care about whether or not you can play your instrument.”