Produced By: Kelsey Bolar and Andrea Mew

Written By: Andrea Mew

Disclaimer: This profile includes explicit language that may be considered profane to some readers. Reader discretion is advised.

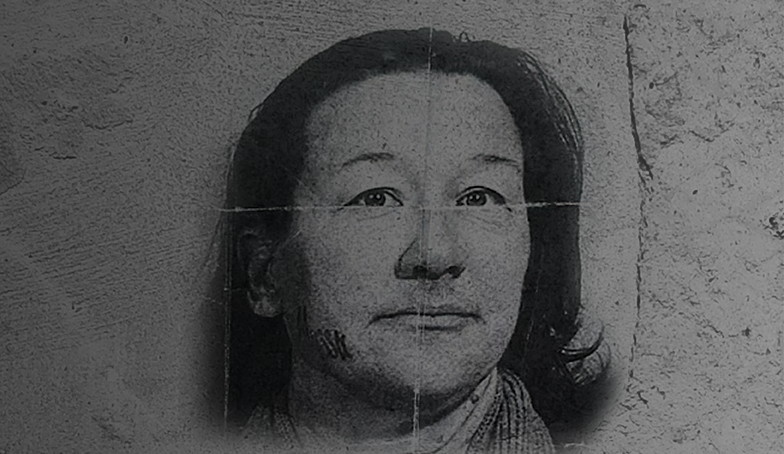

Alissa Kamholz suffered such abuse growing up that when she was sentenced to prison, she called it “my safe place.” During her childhood, Kamholz’s mother got remarried to a member of the notorious Hells Angels motorcycle gang and, as a wedding present, she said, “my mother gave me to him.”

“For 10 years, I was violated continually by him and his biker buddies,” she said in a phone interview with Independent Women’s Forum from Central California Women’s Facility (CCWF).

After their founding in the mid-20th century, the Hells Angels made a name for themselves, sparking riots, trafficking drugs and other stolen goods, gunrunning, committing violent crimes, and assaulting and gang-raping strangers or their members’ own girlfriends and family members. Kamholz was one of these victims. The perpetrators, she recalled, were long-haired white men.

So when she was sent to prison under California’s three-strikes law to serve a sentence of 39 years to life, she said she finally felt safe from the men who routinely abused and robbed her of her innocence from such a young age.

That is, until California’s Senate Bill 132 went into effect, allowing inmates to pick their preferred housing based on “gender self-identification.” Under this new law, men affiliated with Kamholz’s stepfather’s gang transferred into the women’s prisons.

Kamholz had already spent over two decades at Central California Women’s Facility (CCWF) when, in November 2023, a long-haired, white male inmate was placed in her room.

“It was a very, very difficult situation for me,” Kamholz said. She asked the man to have a private conversation with her in their dayroom so she could share her extreme discomfort with the situation as a victim of abuse, as well as the discomfort of the other women in their unit. Allegedly, he told her that he would be uncomfortable too if he was in her place, so he said he would move.

“Well, then,” Kamholz said, “he decided he wasn’t going to move,” which triggered a state of panic.

Kamholz told IWF that she has PTSD from her past abuse, which causes nightmares that come and go. With this man living in her room, she said that her nightmares got worse.

“It was very hard for me to sleep. I didn’t want to take a shower, I didn’t want to use the bathroom,” she said.

Then, in conversation with her male roommate one day, Kamholz found out he was from the same small town that she was from. This piqued her curiosity, so she asked if he knew of the clubhouse where she had been routinely abused. To her dismay, Kamholz said he knew exactly where this clubhouse was and that it was his frequent hangout spot.

“I know he wasn’t one of my own abusers because he’s only, I think, seven years older than me,” Kamholz said. “But there’s a 97% chance that [he was] there in the building or even the room while I was being raped and stuff.”

For Kamholz, being housed with a man who had such intimate ties to her abusers was the hardest situation she’s ever experienced.

“I feel like even being sentenced to prison was easier than having to deal with that,” she said.

After three weeks of living with this man, Kamholz alleged he exposed himself to her female roommates while she wasn’t there. Her roommates reported this to the correctional officers, and staff moved him out of their room. But this move, she added, ended up being a “reward” for the inmate’s “bad behavior.”

At CCWF, there are special housing units for inmates exhibiting good behavior: an honor dorm for inmates who are two years write-up free, and a pre-honor dorm called the RPU (short for Rehabilitation Programming Unit) for inmates who are six months write-up free.

Kamholz explained that when her roommates reported their male roommate for exposing himself, the staff moved him to the pre-honor dorm.

“Then once he was in here,” Kamholz said, “he choked out one of his roommates and beat up the other one. They went and reported it, the alarm got pushed, everything, and they rewarded him by moving him into the honor dorm in his girlfriend’s room. It’s ridiculous.”

Kamholz was part of CCWF’s Inmate Advisory Council, previously known as the Women’s Advisory Council. Its name was changed to be politically correct and to take into account the now-mixed-sex facilities as a result of SB 132. The council serves as a liaison between administration, staff, and population staff.

She explained that while she was the yard chairperson during COVID-19 quarantines, she was called to participate in a Zoom meeting with the transgender-identified inmate population from San Quentin Rehabilitation Center—California’s oldest prison and the state’s only death row for men.

It was during this Zoom meeting that Kamholz first learned about how male inmates identifying as transgender were going to start transferring to their single-sex, women’s facility.

“I feel like Newsom just snuck that in while everybody was so focused on COVID,” Kamholz said. “We were told ‘this is what’s happened and it’s not going to change, and we’re not asking your opinion.’”

Kamholz said that she and the others in her council brought up their concerns about male criminals gaining access to female prisons, but that the administrators dismissed their concerns, telling them that none of the men would be members of security threat groups, above a “Level II,” or have crimes against women. Kamholz claims she was also told male inmates moving to female prisons would be on cross-sex hormones and would have undergone surgeries.

But once they arrived, she said, “Almost all of them are members of security threat groups. A large majority of them have crimes against women or children, and they’re Level IVs.” She continued:

“They’re very honest once they get here. They’ll say, ‘I’ve been down all this time. I’ve exhausted all my appeals. I’m never going home’ and—excuse my language—but they say ‘We just want pussy.’ And so that’s what we’ve been dealing with.”

In Kamholz’s opinion, female inmates are held to standards that do not apply to males who identify as transgender women.

“The men can do anything they want. They can look any way. They can dress any way. I mean, there’s one that walks around with his shirt tied up like it was a halter top,” Kamholz said. In contrast, she asserted, female inmates are expected to wear clothing that conceals their curves, keep their nails short, and if they wear makeup, it’s expected to be neutral or skin color.

She said that the whole situation has felt “very isolating,” as many organizations that traditionally stand for the rights of female inmates are now working against them, in favor of men.

“It’s a really horrible feeling to feel powerlessness and isolation to the extreme,” she said. “Our sentence wasn’t to be abused. We were supposed to be … rehabilitated, and so everybody’s turned their back on us.”

California recently implemented a new model for practices and principles within the prisons to reform the criminal justice system. The “California Model” functions similarly to Scandinavia’s setup of rehabilitation over punishment. The California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation has even published video spotlights of CCWF as a prime example of their “commitment to rehabilitation, positive experiences, and transformative change throughout the prison.”

But now, Kamholz said that female inmates aren’t actually able to get the rehabilitation they need because they’re forcibly being housed with male criminals, many of whom, she said, are manipulative and even predatory.

“People are already getting raped and nobody cares,” Kamholz said. “Honestly, someone in here is going to end up getting killed.”

As it currently stands, Kamholz is set to be considered for parole in 2032. Though many incarcerated women understandably fear speaking out about the male takeover of female prisons—as some have explained to IWF that this can jeopardize their safety or even parole eligibility—Kamholz wanted the public to hear what’s really happening to women behind bars.

“My voice is my weapon and I’m not afraid to use it,” she said. “I am not scared to speak out because, I mean, there’s nothing worse that you can do to me.”